The more you travel and explore places, the more you question concepts like nationalism and identity. What is Nationalism? And how does it bind people and cultures? And what is an identity? How does it gather shape, and how significant is it? My visit to West Bengal and Assam made me revisit these questions and made me wonder how concepts like nationalism and identity fit in the larger heterogeneous, complex and interwoven identity of the Indian subcontinent.

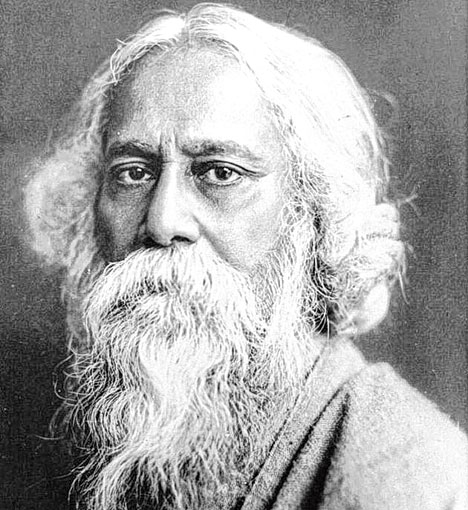

“Can you name the person who has written the national anthem of two countries?” Flashback 2009, Genetics class, University of Houston, Clearlake. The person who asked this question, our professor, was from Bangladesh. After some brain-racking moments, he answered, “Rabindranath Tagore!” Many ‘wows’ were exchanged, especially from American students. But my passion for history made me ask,” But Professor, Tagore died in 1943, and your country was created in 1971. How did he write your anthem?” Seeing the professor taken aback by my response, there was a burst of mild laughter in class. After a few moments, he regained his composure. He admitted that I was right, but stressed that Tagore is their national icon, to which I remained adamant and repeated that his domicile was Indian, as there was no Bangladesh when Tagore was born. Our conversation ended in a friendly truce, but it was my first exposure to the Indian subcontinent’s complicated struggle with identity and nationalism. I was an ‘Indian nationalist’ then, but as I reflect on this incident after a decade, I concede that I have no nationalism and urge for identity left within me. I have concluded that this region is to be enjoyed and appreciated by its diversities and interwoven complexities!

Some years back (circa 2016), the Indian Prime Minister visited Bangladesh, and as part of the ceremony, national anthems of these two countries were sung. It was an overwhelming experience to witness how one man – Rabindranath Tagore – was honoured by both the countries through the ceremony. India’s national anthem is in Bengali, which is one of the many languages of this country. In contrast, Bangladesh’s national anthem, in Bengali, defines their national identity, after their ugly breakup with an Urdu-imposing Pakistan. I recalled my conversation with the Bangladeshi professor and conceded that it is language, and NOT religion, that binds people from this region together. To stress my point, the professor from Bangladesh was a Muslim, but his claim on Tagore was based on his language, and not on his religion. After the lecture, he had told me that, “we Bangladeshis have cherished and nurtured Tagore more than you Indians.” It was no wonder that after the national anthems, the Indo-Bangla ceremony also witnessed singing of ‘Ekla Cholo Re.’

As I witnessed the ceremony, I was attracted to Bengal, and it became one of the places in my travel wishlist. A short trip to Bengal and Assam two weeks back made me set my feet on ‘Amar Shonar Bangla’ – My Bengal of Gold! I was attached to this land of gold through music because of the galaxy of stars it has produced. Allauddin Khan, Enayat Khan, Annapoorna Devi, Ravi Shankar, Ali Akbar Khan, Vilayat Khan, Nikhil Banerjee, Swapan Chaudhari, Anindo Chatterjee, Kumar Bose – the list is endless! However, many musicians in this list were born in present-day Bangladesh. The music which they practice is undoubtedly Indian classical music, and present-day Bangladesh also recognises them as musicians who practice Indian music. However, the music of Bangladesh is Baul, ‘Rabindra Sangeet’ and ‘Nazrul Sangeet’ which is also practised in India’s West Bengal. Bhatiyali, the song of the fishermen and boatmen was popularised on the concert platform by Nikhil Banerjee and Vilayat Khan (Indian musicians) and it happens to be the national folk form of Bangladesh.

This region is so fascinating that Bangladesh (an independent nation) is sandwiched between two Indian states, West Bengal (on its west) and Tripura (on its east) with music, instruments, fabric, language, fish as binding factors! How will nationalism matter to people in such a place, and what will distinguish an Indian living in West Bengal or Tripura and a Bangladeshi? The great man Tagore towers over this region, and after a decade, I now understand the love and affection of the Bangladeshi professor for him. I have shed off my nationalist pride as well, and I do not ‘restrict’ Tagore to India.

However, I end this note by expressing pride for India’s commitment to Secularism, and it remains the binding force for everyone to coexist in the subcontinent. Muhammad Yunus, an eminent Nobel prize-winning economist from Bangladesh, writes the following in his autobiography:

“We were all deeply committed to partition from the rest of India. When my brother Ibrahim started to utter his first words, he called the white sugar he liked ‘Jinnah sugar’ and the brown sugar which he did not like ‘Gandhi sugar.”

This was 1947. In 1971, Bangladesh was separated from that very Pakistan which was created by the same Mohommad Ali Jinnah, who was the favourite of Yunus’s brother (and many people who supported the partition on religious lines). The new country adopted Tagore as its icon who was undoubtedly closer to Gandhi (than Jinnah), the same man which Yunus’s brother (and many others then) did not like. The ‘India of India’, on the other hand, lives on!

(P.S: I have immense respect for Muhammad Yunus. After all, the ‘Land of Gold’ has three Nobel Prize winners in Economics – Amartya Sen, Muhammad Yunus and Abhijeet Banerjee).

Image Credits: https://www.telegraphindia.com/states/west-bengal/tagore-and-rolland-invoked-in-troubled-times/cid/1415897